Ten months after the Supreme Court confirmed trans-identifying men are not women, the campaign group For Women Scotland were back in court today aiming to give the Scottish government another shoeing.

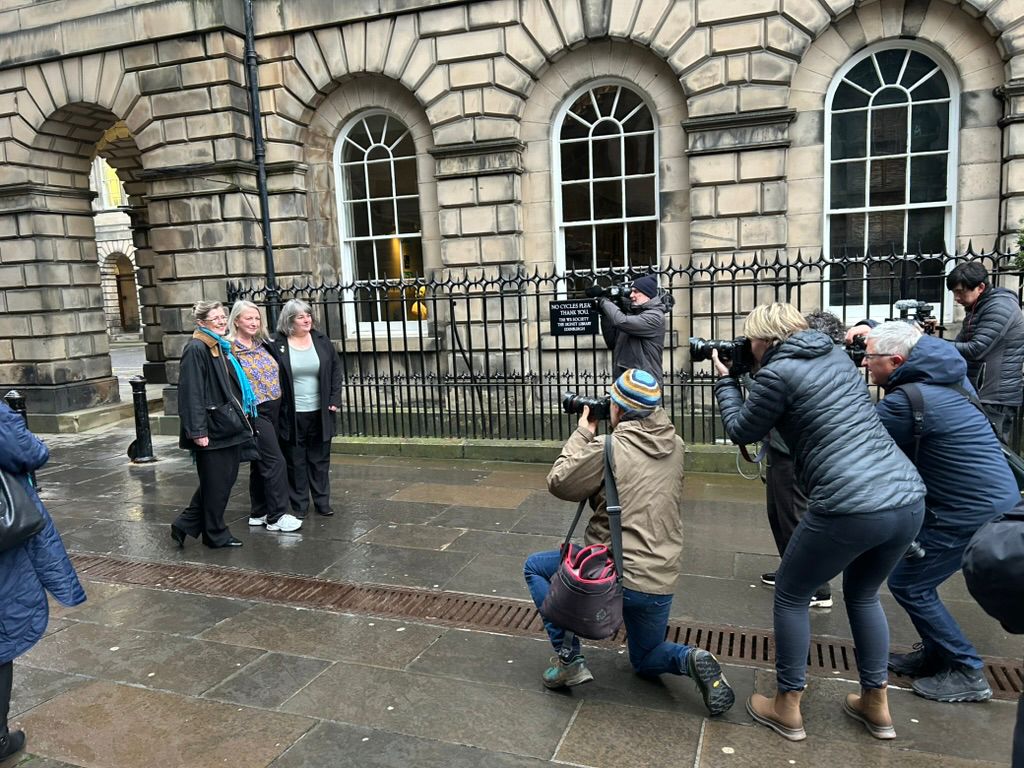

This time Trina Budge, Susan Smith and Marion Calder were at the Court of Session in Edinburgh, seeking to have the Scottish policy of housing men in women’s prisons declared unlawful. As per the Supreme Court case, the Court of Session has allowed two intervenors to make arguments – the Equality and Human Rights Commission (which covers England, Scotland and Wales) and the Scottish Human Rights Commission, which – oh you’re ahead of me. The case is being heard by Lady Ross.

Today we heard from the FWS barrister Aidan O’Neill KC, who could not hide his contempt for the Scottish government nor the SHRC’s arguments. He said he was struck by the Scottish government’s “lack of legal substance in their case” saying that despite the government’s argument that they were “required” by Human Rights law to put some male prisoners in the female estate, “there is no case law from the European code of human rights to that effect”.

Instead, he claimed, the Scottish government and SHRC had resorted to (what I managed to spell incorrectly on twitter twice) “prestidigitation” – that is, legal “sleight of hand” designed to distract from the fact they had no case. “You’ve come into the conference chamber naked,” he taunted his opponents, “without the case law to cover your embarrassment.”

O’Neill pointed out the “extraordinary” terminology used by his opponents, in which people are either “transgender women” or “non-transgender women”. He took this to mean that in their terms, the judge “is not a transgender woman, but is a non-transgender woman” and that he was “not a transgender man, but I am a non-transgender man, but I’m not a non-transgender woman”.

O’Neill said his own arguments offered a model of clarity. He had three propositions:

- The Scottish Prison Service is obliged to provide women-only prisons.

- Women-only prisons mean you get no men in them.

- The SPS policy at the moment says you can put some men in women’s prison, which is unlawful.

“I should really sit down at this point” said O’Neill, “because there’s not really much more to the case than that.”

“And yet you wanted seven hours”, said Lady Ross, drily.

O’Neill said he was obliged “to cover every base” just in case the court found itself “misled” by the Scottish government and their barrister Gerry Moynihan KC, who, O’Neill predicted, would spent six hours on his feet “making things up”.

“Mr O’Neill…” warned the judge.

Human Shields

The FWS barrister told the court it was a known fact that male murderers, torturers and sexual abusers (of other men) were currently being held in the female estate. These people had all been risk assessed and could now share facilities with women. O’Neill took the judge to a sworn affidavit from Rhona Hotchkiss, the former prison governor who reported that female prisoners experienced “threatening behaviour” from trans-identifying male prisoners, feeling “unnerved or triggered, by salacious, sexualised comments”. Hotchkiss also reported female prisoners heard “males claiming transgender stages being open about the fact that they were not transgender before being apprehended, and had no intention of being transgender after liberation”. He told the court that “if that’s where your case by case individualised assessment gets you, there’s something wrong with it.”

O’Neill said there was no good reason for treating female prisoners as “human shields” to an ideologically driven policy which did not take into consideration their human rights.

O’Neill said the solution was simple. Keep trans-identifying men in the male estate, and if they are not safe from other men, house them separately. That is apparently the policy in England and the policy in Scotland when dealing with other categories of prisoner who might not be safe in the main male estate.

O’Neill made much of the fact that four in five male prisoners in Scotland claiming transgender status were housed in the male estate and that this seemingly wasn’t a problem for their human rights. Or, in other words, “it’s not incompatible with their convention rights that they be kept in a male prison.”

No Complaints

The FWS barrister then went on to attack the Scottish government’s argument that they’ve had the trans-identifying-men-in-women’s prisons policy for 20 years and no one’s complained about it, so it must be lawful. O’Neill described female prisoners as an “incredibly vulnerable” cohort who could find themselves on report for “misgendering” a prisoner if they called them a man. He said female prisoners existed in a “gaslighting culture” which forced them to pretend a man was a woman to the detriment of their mental health. “Gaslighting’s bad enough when you’re out and free and can make your own choices and can get away, but this is gaslighting while incarcerated, and gaslighting under threat of a sanction. Women are being psychologically manipulated into questioning their own sanity or ability to reason by this policy”, argued O’Neill.

The idea that a female prisoner could bring a legal complaint against the Scottish government was a “massive challenge” and for the government to try to dismiss For Women Scotland’s case on the basis it didn’t feature any female prisoners was in O’Neill’s view an “abuse of process on their part”.

Regarding the feelings of female prisoners who say they don’t mind men in their spaces, O’Neill said that missed the point. “The fact that some women might not feel threatened or whatever, does not take away from the fact that we have separate prison estates for reasons which are entirely clear, which are to do with the right of all women who happen to be in it. The fact that some women are robust enough to be able to cope with a trans-identifying man next them does not take away from the fact that as a group, women are entitled to and deserve protection.”

O’Neill cited a report which stated there was a “routine institutional contempt for women” in Scottish prisons and that the failure to lawfully protect them as a group from the presence of men as a group was one such example.

We then moved on to the reciprocal lawfulness or unlawfulness of housing a trans-identifying woman in a female or male estate. I suspect it is going to form a large chunk of the Scottish government’s arguments. What if a muscular bearded female, high on testosterone, with a double mastectomy and phalloplasty was causing distress and fear within a female prison? Didn’t FWS’ arguments mean that the prisoner should stay in the female estate because it would be unlawful for her to be moved to the male estate.

O’Neill said this was a false equivalence. “This hypothetical really threatening transidentifying woman were to terrify other women, such that it was a proportionate response to remove her from the female estate – that’s allowed for in law, but that doesn’t mean to say that therefore you cannot have women-only estates. Just because some women, because of the gender reassignment, might conceivably moved out of it. It doesn’t make it any less of a woman only estate.”

O’Neill brought the argument back to reality. “What makes it not a woman’s only estate”, he said, “is if you put men into it. That’s the problem.”

The Authorities

O’Neill quoted at length from a number of relevant authorities. One of the most thoughtful was a section from the recent Darlington Nurses judgment. It reads:

“We accept – as does the Respondent [the NHS] – that women are more likely to have experienced sex-based harassment and sex-based violence than men. It will come as no surprise to anyone that this is so. The risk posed to women generally by this state of affairs causes a reaction in many women and leads them to adjust their own behaviour according to the circumstances. Women do not have to experience sex-based harassment or violence personally. The experiences of some women can and does have an impact on others. Depending on the circumstances, a woman might experience fear and distrust in the presence of a man even though, objectively, as a matter of fact, the man is an entirely innocent actor. We take an example that we can all recognise, of a woman walking alone on a street at night, whereupon she notices an approaching male. She crosses the road to avoid the man, holding her keys in her hands in the event she needs to defend herself or she phones someone or pretends to do so. The approaching male is a perfectly decent and innocent person with no intention to harm anyone and is oblivious to the woman on the street. He would feel offended at the thought that someone might regard him as potentially harmful. But it is not the individual’s character that dictates the reaction in the woman. It is not the man himself but the fact that he is a man. The difficulty for the woman in this example is that she is unable to police the character or the intent or motivations of the approaching male. She is fearful of the risk presented in the knowledge of women’s experiences in life generally. Her reaction does not depend on personal experience, although of course it may be explained by this. The Tribunal is able to draw on its own experiences of life in recognising these fearful, defensive, precautionary traits in women in certain circumstances. They are not irrational reactions. On the contrary, they are entirely rational, based on the lived experiences of other women generally. Many women will feel anxious and may take extra precautions in what men might regard as normal situations. Just as the innocent male on the quiet street may say that he has done nothing to generate the fear of the approaching female and that he is offended at the thought of her crossing the road or preparing to defend herself, Rose Henderson [the TIM at the centre of this case] may feel offended by the reactions of the Claimants to their presence in the changing room. But the reactions are real in both scenarios. In the circumstances that prevailed in this case (where employees were required to change their clothes in a communal changing room shared with a member of the opposite biological sex), we accept that a greater proportion of women would experience reactions of fear, distress or humiliation. These reactions, when compelled (in the sense used by Professor Phoenix [an expert witness in the case]) to be in a state of undress in front of men or to observe men in a state of undress are, in the case of those who experience them, not irrational or disproportionate responses. We accept that these reactions/responses are not simply historic and that they prevail and that they are likely to prevail whether the biological male identifies as a woman or not. On the facts of this case, it is only the fact that the biological male identifies as a woman that enables them to gain access to the changing room in the first place, thus generating the fear and reactions of the sort discussed by Professor Phoenix. There is no reason to suppose that the mere fact that Rose has the protected characteristic of transgender status means that those reactions dissipate or evaporate and, on the facts of this case, they clearly did not.“

O’Neill also read from Rhona Hotchkiss’s affidavit:

“Housing male prisoners, including men who identifies transgender with women in my experience, poses serious risks to the well-being of these women. Not all transidentified males pose an overt threat to the physical safety of all women, nor do males in the general population. But we still have sex segregation in key spaces. However, All transgender identified males pose a threat to the mental well-being of a significant number of women, and some also posed a physical threat. All transgender identified males pose a threat to the mental well-being for women. “

Reflecting Hotchkiss’s statement, O’Neill said “This is not fantasy. This is grounded in fact and experience. As a prison governor. And the Scottish Prison Service know this. But still, they will insist that among this group of highly vulnerable incarcerated women, there are then placed men, who… have been sent to prison for the most serious crimes of violence, including torture and murder. And those men are, for the most part, bigger, stronger, more physically dominating than all the other women amongst whom they have been placed.”

Self-harm

O’Neill read out some statistics. “In a study of 109 women across 4 prisons of Scotland… 98… reported mental health, anxiety, depression, or a combination of both. Mental health is the most commonly self-reported health problem… In the same study, 78% reported a history of significant head injury, of whom 40% had associated disability.”

He went on. “One study in Scottish prisons found 85% and 92% of women had experienced childhood and adulthood traumatic experience respectively. 61% of women met the diagnostic, diagnostic criteria for PTSD… 60% had committed at least one offence. 58% of the same sample had self-harmed.”

“That’s the women” said O’Neill “that they are placing, men who’ve been convicted of assault, torture, and murder, to live with them.”

At the end of the day it is the best legal argument which will hold sway, and the FWS legal argument is that female prisoners are lawfully entitled as a group to single sex accommodation. They are protected as a group. Their heightened vulnerability is such that Scottish government has a statutory duty to supply secure single sex accommodation. In April last year the Supreme Court made it clear that such a single sex service can only be provided by excluding all males from it, regardless whether they have a Gender Recognition Certificate or do or do not claim the protected characteristic of gender reassignment. A policy of allowing males into the female estate therefore has to be unlawful, and all of the above supersedes any competing human rights claim an individual trans-identified prisoner might have, both in law and in the application of the law.

The arguments continue tomorrow. If you would like to read For Women Scotland’s Petition and Note of Argument in this case, you can find them here. If you would like to read the Scottish government’s Answers and Note of Argument, you can find them here. I have approached the EHRC and the SHRC for their submissions. If you would like to read all my live tweets from today you can find them formatted into one web-page here. Thanks to everyone who donated today as I tweeted. I appreciate it.

Please note I do not have the copyright ownership of any of the images used in this piece. I therefore cannot give you permission to lift or use them, but this blog post can be shared in its entirety in the normal way.

Comments are moderated. Please keep it interesting and informative rather than abusive and defamatory. If you would like to support my work with a one-off donation and receive the Gender Blog newsletter in your email inbox you can sign up here. Your email address will be stored securely and confidentially, never given to a third party and will only be used to inform you about things I think are interesting.

Leave a Reply